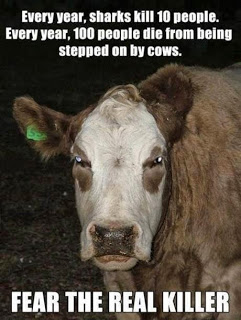

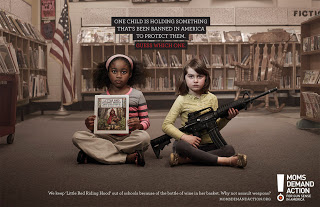

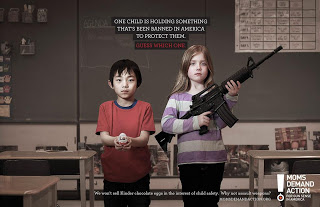

You know that execution where you combine two

elements to create one message? They're the zenith of simplicity, and I think we need more of them.

This technique, which unites the product with a symbol (Known as a schema in psychology) to create the message, has produced some of the most memorable ads in

history, and yet oddly they are slowly disappearing.

Presently, there's two forces leading to the demise of these simple tactical ads:

1. Clients are scared about the economy and want (what they consider) 'risk-free' ads.

2. We've become so preoccupied with applications, gamification and digitisation that we're forgetting the effectiveness of simple advertising.

In client-land, an advert that communicates anything less than 5 messages at a time is considered a waste of space. We've all come across the client that erroneously thinks the more information there is in an advert, the more the consumer takes out of it.

Just like, we've all received the 'digital' brief, when a great print ad (like the ones above) is the better option.

We know that bombarding a viewer with multiple messages and information only encourages them to turn their attention away, and that, because it has a much greater chance of being processed and subsequently remembered, communicating a single crystallised message is far more effective.

This clash of understanding, in my opinion, is why we end up banging our heads against a wall, trying desperately to help the client help themselves, while they're completely aloof.

The type of execution I'm talking about here, and shown above, is the pinnacle of simplicity. These are the ads that celebrate creativity, and are very powerful, both, with advertising effectiveness and in their capacity to win awards. No laundry lists, leaderboards, likes or QR codes needed.

Here's some reasons, for my part, as to why these sorts of executions work:

1. Simplicity.

Keep it simple stupid (KISS), we all heard this one at school. These executions treat the audience with respect. It's not spoon feeding them the message, and as a result they engage with the brand and spend more brain time with it.

1. Dwell time.

The fusion of the 2 objects getting perceived at the same time creates a visual puzzle that, providing you’ve done your job right and the symbols aren’t too abstract, the viewer will want to solve. This is dwell time. The longer the viewer spends interpreting the message, the more likely the advertising will be effective.

2. Likeability.

I think these ads are simply likeable. They reward the viewer for looking, as the viewer receives that wonderful ‘Aha’ moment. They get in on the gag, and this cognitive effect connects them with the brand.

We're currently going through a phase where things are becoming unnecessarily complicated. Fusion, unification, combining, bonding; whatever name you have for this execution, is a great technique to create simple award-winning adverts. Who doesn't want that?